Somewhere along the line in the early evolution of hip hop, an idea was formalized: MCs rap over a beat loop created by a DJ playing two copies of a record that features an open drum break over and over again on two turntables. Considerations of the originators and early practitioners aside, that idea is sacred to me. It’s beautiful. It’s genius. To me - and I don’t expect anyone to agree with me - it’s quintessentially what hip hop is. Boil it all the way down and building blocks of hip hop are the breaks. The breaks, the breaks, the breaks.

The very first song I ever recorded was built on one of the all-time classic drum breaks: “The Jam” by Graham Central Station. The vast majority of songs I’ve ever recorded were built on a drum break foundation. It may surprise you to know that even a song like “Blood Of A Young Wolf” is built on a drum break (I’d rather not say where that one comes from).

Obsessed with The Idea, I started collecting and cataloguing drum breaks in 1989. I strongly believe that at this point - based on my decades of research - that I have roughly 35% of the drum breaks in existence in my personal collection. That may not sound all that impressive. But for many years, I have maintained a data base with a ranking system all known drum breaks. Not all drum breaks are created equal. Some are great. Many are not. I hunt the ones from the top third of the scale. I have nearly all of them. It’s an insane obsession. It can’t be rationalized. My quest is to build the ultimate collection. I guess it’s my way of honoring hip hop. It’s the closest thing I have to religion.

How can I feel so confident in my knowledge of something that seems unknowable? I will explain.

There are all kinds of record collectors. The various types tend to form communities. Folks who come at it from a hip hop background - as I do - are commonly referred to as crate diggers, or just diggers. Through the decades, diggers have congregated in various places. In the old days, it was in-person at conventions (which still happens). But since the advent of the internet, there have been a few different online forums and platforms where diggers gather. These days, the primary location seems to be Instagram. We find each other the same way members of all groups do - with the use of hashtags and the general social currents of online spaces.

Several years ago, I quietly set up an Instagram account under an alias conjured by one of those name-generator things. Random. I had no real plans to post anything at first. I just followed the accounts of big-time diggers so I could learn from them. The spirit of the community is quite fun and positive and so I couldn’t help but to want to get involved and contribute. After thinking about it for a long time, I came up with a plan to showcase my admiration for The Idea.

Every week for the last two and a half years, I have posted a 60-second video. Each video is soundtracked by a highly composed mix of drum breaks. As it turns out, 60 seconds provides enough time to showcase seven records. Seven seems to be the magic number.

I have a document with thousands of drum breaks organized by tempo in beats per minute. Each week, I chose a BPM and then choose seven records from my collection in that category. I then spend seven days crafting the mix. I’ll be the first to admit that it’s insane. I’m almost always working on these things. I pride myself in putting the highest possible production value into each mix. They’re all detailed with samples and scratches and assorted references to hip hop history. I have become a monk.

There is a master plan with a road map. To execute the entire plan - which has already been scripted in full - my work will take me into the year 2024, at least. What will the body of work mean when it has been completed? I have no idea. But it will be the master work of my life - something I will have worked on every day for at least four years when all is said and done (if it ever does end).

I have immersed myself fully in what I see as the holy waters of hip hop. Is it something akin to the spiritual journey of Siddhartha? Why the hell not? To me it is. I mean, not really but sorta.

Through feedback, interaction and relationship-building on Instagram with most of the heaviest diggers in the world, I’m very confident in my knowledge of drum breaks even though I’m still learning new things all the time. I’m now in the fortunate position where many diggers will share the findings of their archeology with me.

I’m not telling you all of this because I want you to follow my Instagram account. I don’t. It’s a private account and with very few exceptions, I only allow through the doors those who I believe I can learn (about drum breaks) from. It’s a small group. And less than ten of my followers know I am Buck 65 (I assume the vast majority have never even heard of Buck 65).

I tell you all of this because the weird quest I’ve been on has altered me in a rather profound way. It has changed the way I see, hear, understand and appreciate hip hop. I guess it has purified me, in a sense. And it certainly shaped the sound of my new album in a deep way. Practically everything else has been stripped away. The Idea is what I am as a ‘musician’ now (or whatever the hell you might call what I’m doing).

As far as how I’ve come to see hip hop (and again, I don’t expect anyone to see it the same way)… If in its essence the drum break is the foundation, then it existed in its purest form in two eras: before the recorded era in the 70s (refer to the YouTube video imbedded above) and in the so-called “Golden Era” - in the time between the advent of sample-based beats and the Biz Markie lawsuit, which - for all intents and purposes - ended the sample-based era. I’ve seen some mark the era as the years between 1986 and 1996. My definition is a little more strict. I know my opinion on the matter is unpopular (and utterly unimportant) but - thinking back to how it began in the ‘70s - I think the truest thing was when the breaks were unadulterated: straight-up looped rather than chopped up. I’m ALL about those raw-ass drums. So I see the Golden Era as the brief-but-glorious three-year period between 1986 and 1989 (but don’t get me wrong - there are hip hop records from the 90s that I still love and even today I hear the odd thing here or there that lights me up).

So! When I made the King Of Drums album (and maybe now you’re getting an idea of where the title comes from), I followed two sets of blueprints: one from the pioneering days in the late 70s and one from that ’86-to-’89 period. Basically, I wanted to make a record that sounds like it was made back then but with today’s knowledge and technology.

Nothing I’ve done before sounds like the King Of Drums album. I touched on those ideas here and there with stuff I was doing in the 90s and maybe the odd thing in later years. But nothing like this. And although I’m still a huge fan of groups like the Ultramagnetic MCs and Tuff Crew, I wanted this to be as much my own expression as possible. So if anything, I’d say the biggest influence on the sound of my new album has been the obsessive work I’ve been putting into my Instagram account over the last two and half years. The sound clip embedded at the top of this post comes from that monk work.

I hope what I’m describing sounds even a little bit interesting to you. If not, I realize this will be just the latest in a long series of alienating creative decisions that narrows any audience I may have further still. But just let me say that I believe in what I’m doing now very, very strongly. My conviction has never been this strong. And for as serious as it may sound, I had more fun making King Of Drums than anything before. Based on the feedback I’ve gotten so far, it seems to show. It’s a fun-ass record.

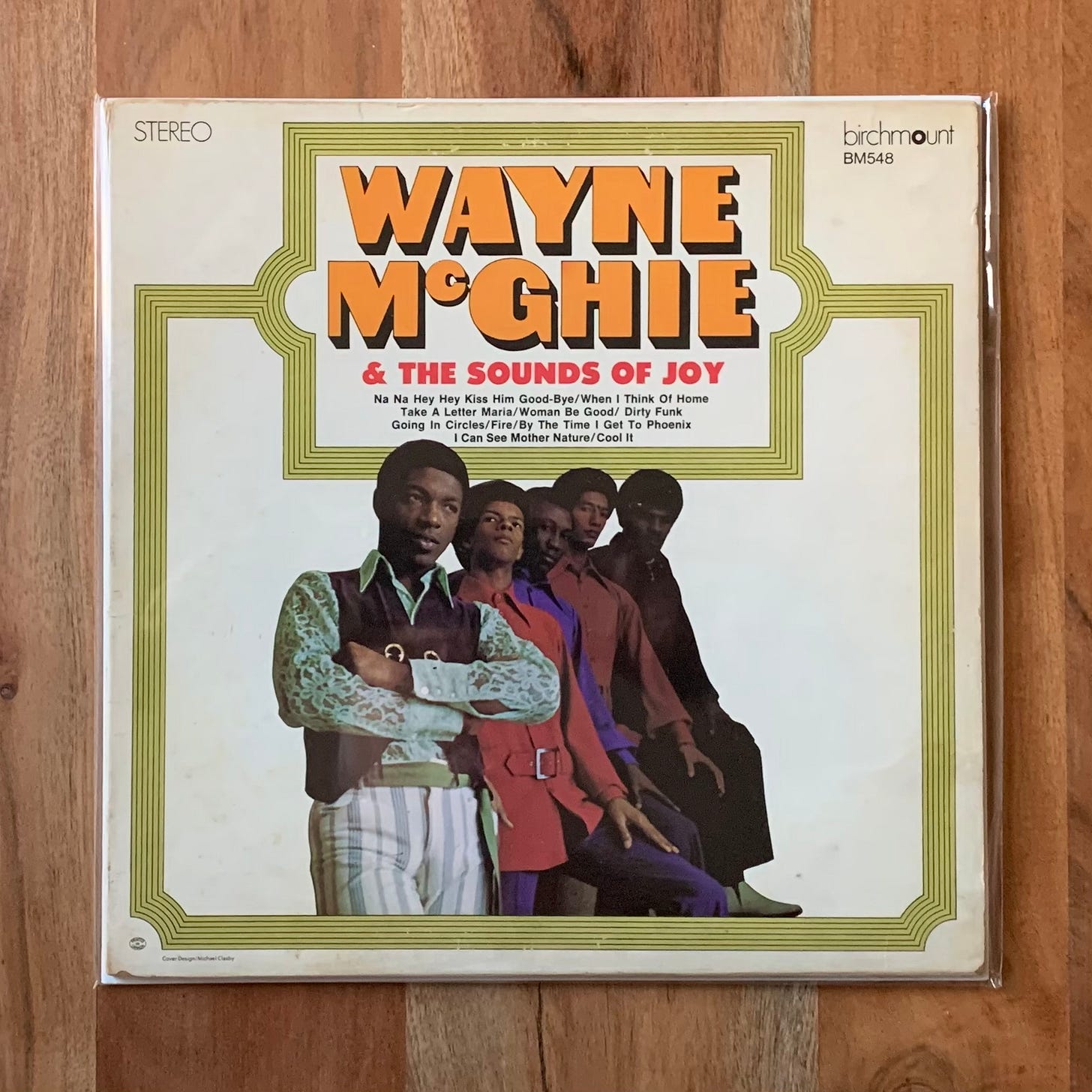

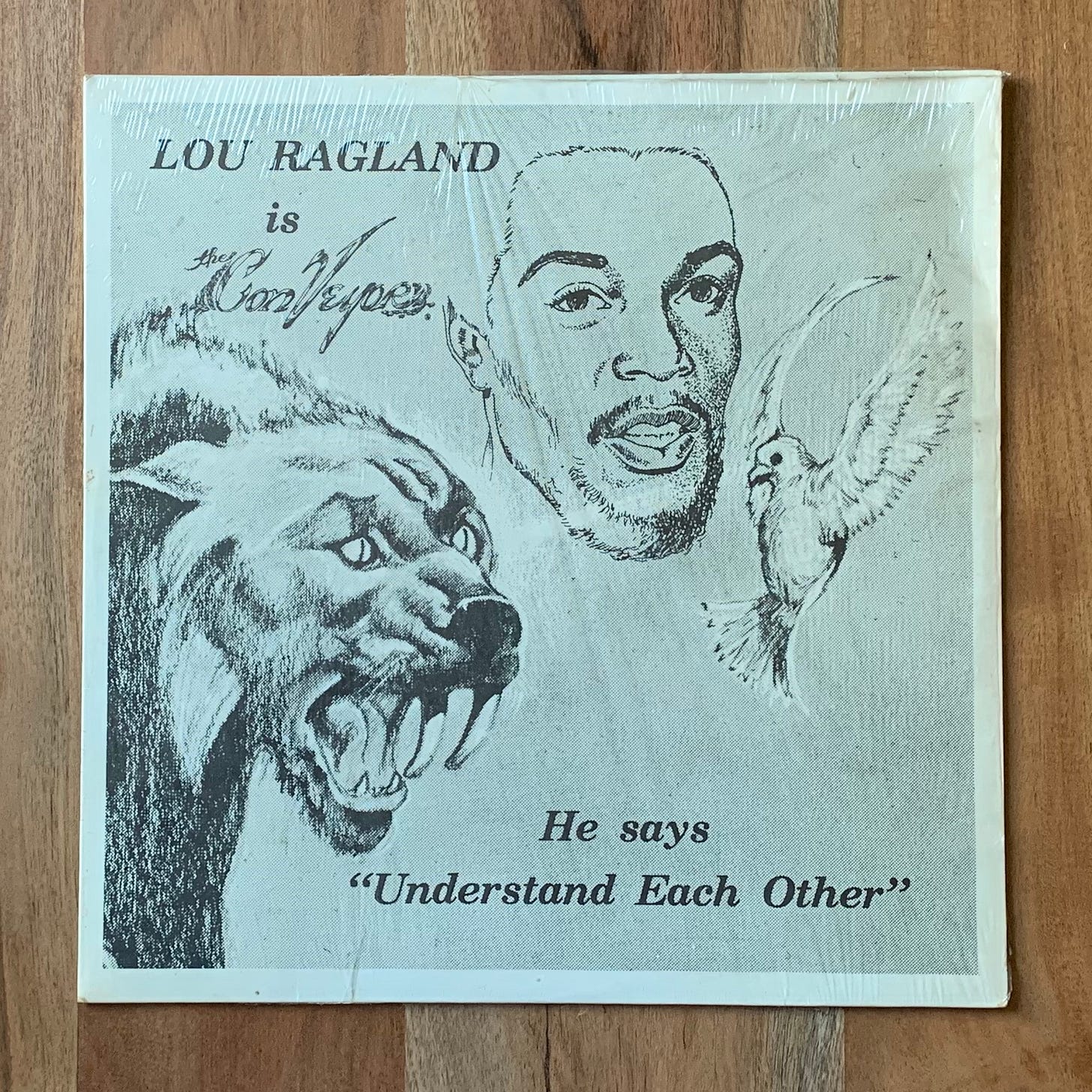

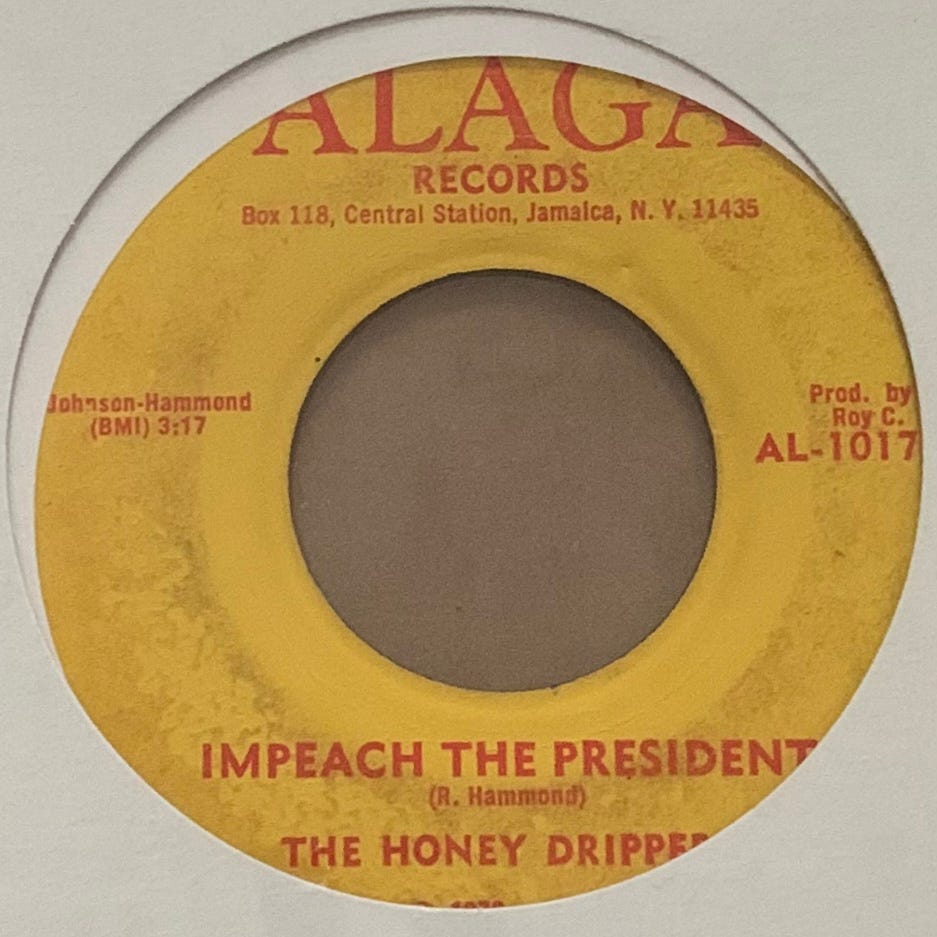

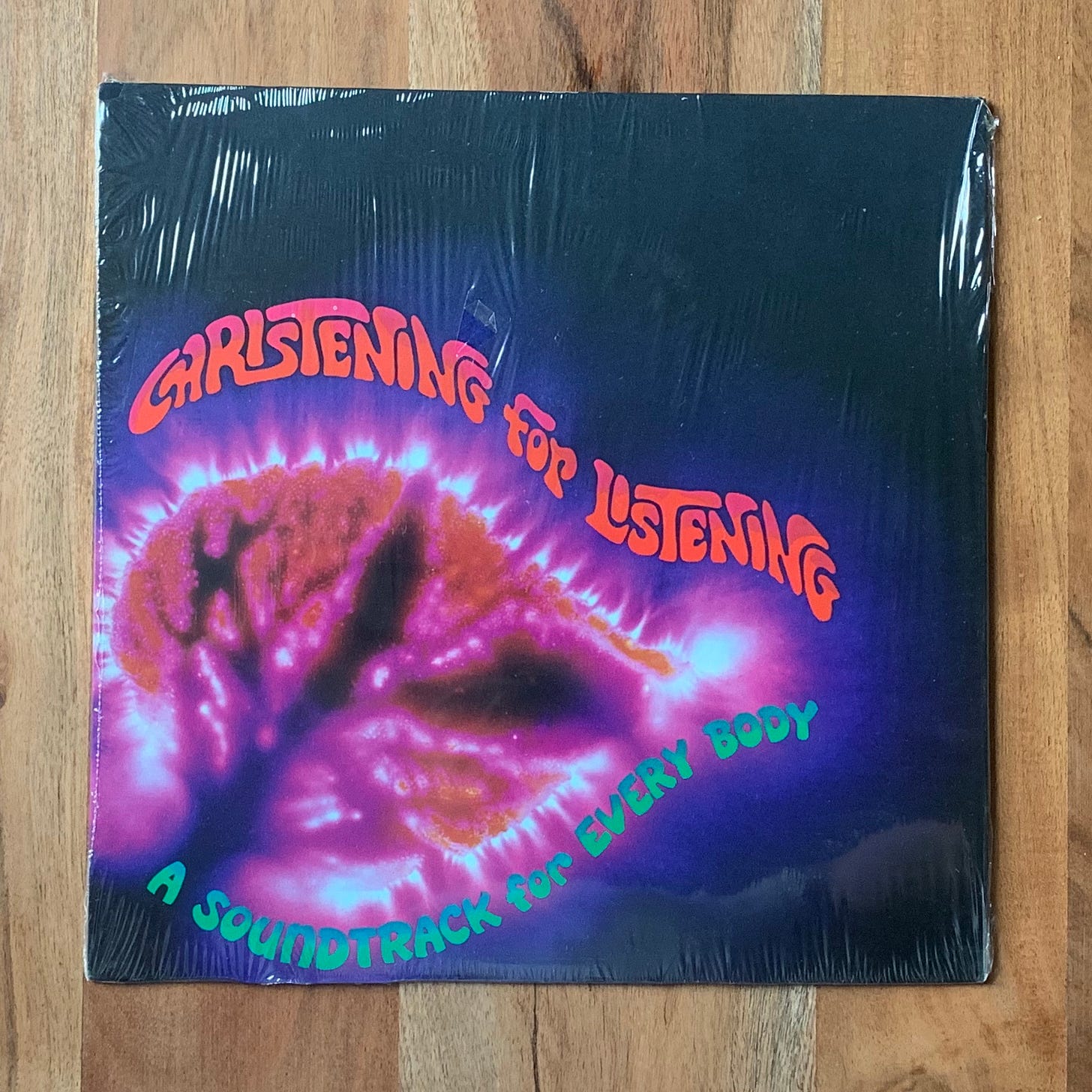

Quick note: all the photos in the post are of records in my personal collection.

More nerdery in next week’s post. Hope to see you then.