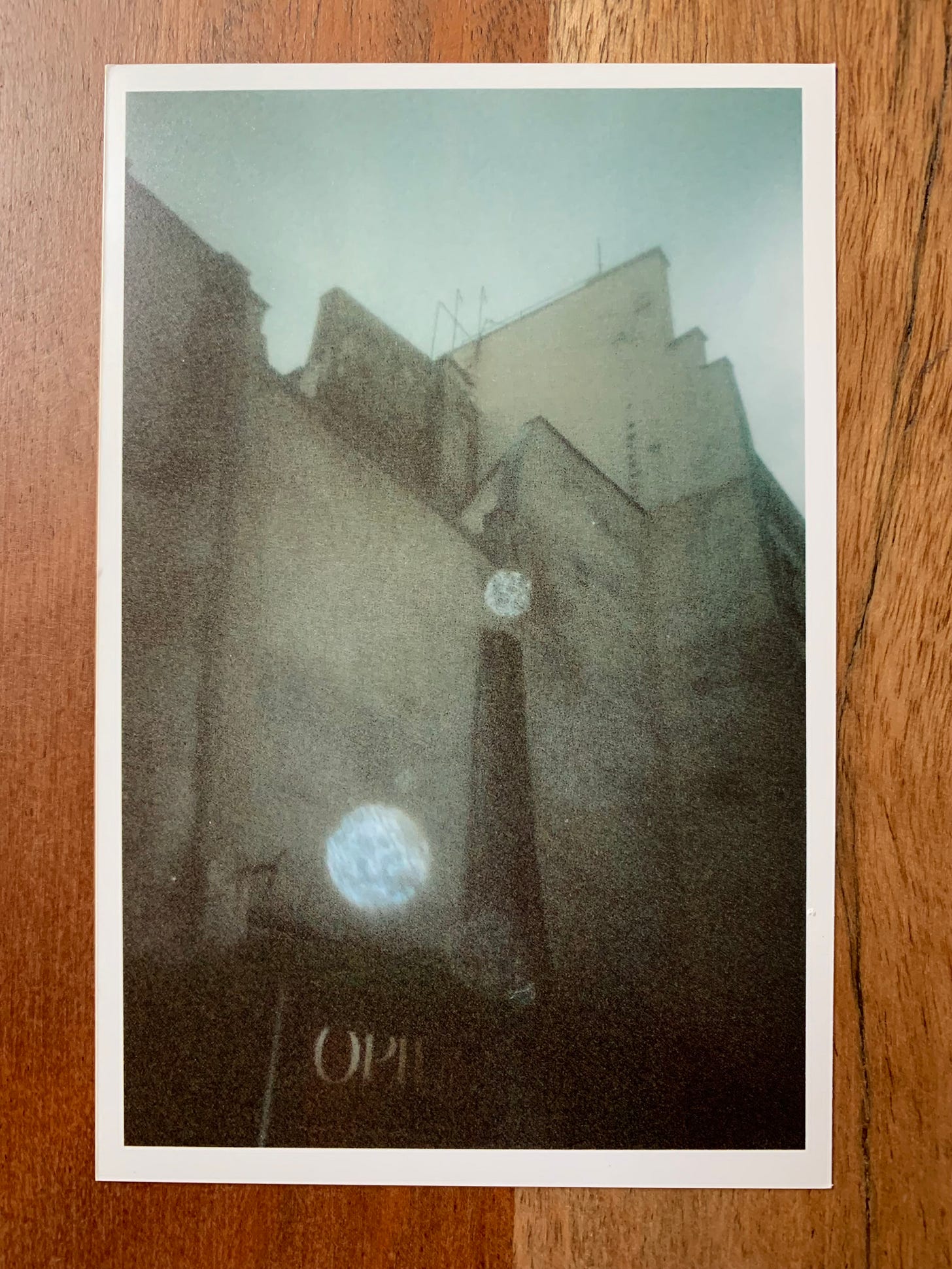

Shortly after I signed my record deal in 2002, there was a discussion with my label about the best way to grow my audience. I believed that what I was doing was very niche and that it probably wasn’t possible to grow my domestic audience much beyond where it already was. I argued that the most logical way to grow things would be to try to expand internationally - to look overseas to try to find more weirdos like those who liked my stuff in Canada and in the U.S. I said that Paris would be a good base of operations for efforts to conquer Europe. I said to the label, “I should live in Paris and you should pay my rent.” To my surprise, they went for it. So from 2002 to 2008, I lived in Paris. I also had a place in London for about a year starting in 2003 and I had a place in New York for a year starting in 2004. It was pretty sweet, I must admit.

So I was living in Paris when I started working on Talkin’ Honky Blues. Paris inspired me in all the old cliched ways and so - naturally - I started reading Hemingway and Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin. You can hear the influence of those writers all over the lyrics of the songs on THB. I was especially inspired by a short story by Anaïs Nin called The Houseboat, which I essentially adapted for the eight Riverbed songs that form a thread running through the album.

The #1 challenge I faced when making THB was the whole sampling issue. No one from my label told me I couldn’t make 100% sample-based music anymore but I knew that attempting to do so would be a problem. I wasn’t operating in the underground anymore. My budget was limited and clearing samples is very expensive. Plus, there’s never any guarantee you’ll get the permissions you’re seeking.

So I started working with musicians. It doesn’t seem like that big of a deal now. When you see big rappers live these days, they’re backed up by a live band more often than not. But in 2002, it still mattered and a lot of people in my core audience hated it. Many never forgave me for it. Ultimately, the plan I discussed with my label to expand my audience worked. With THB, I found a lot of new ears. But I lost a lot too. My audience was starting to change.

The one thing people really freaked out about was the use of the banjo. People reacted to it like it was Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ or something. There are 18 songs on THB. Banjo was used on two of them: “Wicked And Weird” and literally a few notes on “Riverbed 3”. Those who thought it was cool or interesting praised me for it but I’m pretty sure it was my friend Charles who suggested the idea. We tried it. I liked it. We ran with it. People freaked. Banjo aside, there is quite a bit of twangy guitar and pedal steel on the album and I do understand why that came across as sacrilegious to some people. I was attempting to take hip hop music into new territory and it was a trip that a lot of the hardcore/underground heads didn’t want to participate in. That said, I believe a lot of people never got past “Wicked And Weird”, which was released as the first single from the album. There’s more going on than first meets the eye.

One fateful day when I was living in Paris, I received a message from Egon, who you might know from Now-Again Records. Back then, he was helping run the Stones Throw label. He and Peanut Butter Wolf were in town and asked if I was down to do some record digging. We ended up at the flat of the renowned record dealer, Victor Kiswell. Victor and I exchanged info that day and after that, we hung out regularly. I was already a pretty serious digger but under Victor’s tutelage, my game was taken to a whole other level. And I used a lot of the treasures I acquired from Victor on the THB album. In some ways, I’d argue that it’s more of a feast for serious sample-spotters than any album I made before it. And three of the beats on the album were made by the legendary Jorun Bombay, who - for my money - is one of the greatest producers in hip hop history.

Here’s what I don’t like about THB now: in 2002 (or maybe sometime before), I had fallen out of love with hip hop music and you can tell. It was a weird time. I didn’t like a lot of what was going on in the genre in the early 2000s. Hip hop was going mainstream. I didn’t like any of the big records back then and I still don’t. There were a few cool things in the indie world but I mostly didn’t like what was going on there either. I think I must have thought that I couldn’t get away with making the music I really wanted to make. It seemed passé. I thought no one wanted to hear it anymore. And even if dudes like Edan and People Under The Stairs were doing great things, I probably figured I just couldn’t make records that sounded like theirs on a major label. It was a crazy feeling. I had just signed a big deal and the music I wanted to make was kinda dead. So I decided I had to try something new. I started off down a new road that ultimately took me to an unhappy place.

And here’s another thing: as the new direction of hip hop music was leaving me cold in the early 2000s, I started exploring other kinds of music. I got into old folk and country music and post punk and songwriters like Leonard Cohen and Townes Van Zandt. That’s all fine and good. But I started infusing that stuff into what I was doing. I see that as a mistake now. I wish I had just stayed in my damn lane. I took pride in my music reflecting my diverse tastes. Now, that whole thing makes me want to barf. Don’t get me wrong - I still love Townes Van Zandt and Gang Of Four. But the idea that I tried to BE all of those things embarrasses me now. Over and over again, I failed to pull off something that was a bad idea in the first place. That pretty much sums up 15 years of my career.

Quick note on the sound file attached above: this unfinished relic demonstrates how the process worked back in those days. The guitar you hear was a little sketch made by my right-hand man, Charles. I’d add some drums and we’d go from there. In this case, the skeleton was never fleshed out.

After THB came Secret House Against The World, which was the result of a chance encounter. We’ll get into that one next.